"Australian Modernism and MARS"

In the conventional surveys of Australian Modernism to date, the architects of the Modern Architecture Research Society (MARS) constitute what could be described as ‘the lost generation’ of Sydney Modernists. Within MARS, there were enough practitioners to profess to being Modernists as well as practise modernist architecture, and they formed an interactive community of architects who promoted their prewar agenda through professional organisations, journals and political organisations. In New South Wales, MARS pioneered, promoted and produced a place-centred regional modernist architecture. Early MARS work, notably Arthur Baldwinson’s early site-specific methodology, was a unique response to the problems of Australian place-centred residential design, MARS and its members are the catalysts for the later modernist movement currently identified as the Sydney School.

Modernism in Sydney architecture reached critical mass with the formation of MARS in March 1938. MARS’s organising committee included the architect (and later historian) Morton Herman as committee chair, Walter Bunning as secretary and Kenneth Goble, Eric Andrew and Baldwinson as extraordinary members. Baldwinson (UK 1935–1937), Goble (UK 1935–38), Herman (UK 1930–36) and Bunning (UK 1937–1938) had been resident in Britain when Wells Coates, P. Morton Shand and Maxwell Fry founded the first MARS group in London. The two organisations, however, were unaffiliated.

The written aims of Sydney MARS were: to study the aesthetic, structural and sociological problems of the community; to coordinate the ideas and activities to formulate means of solving these problems; and to present solutions to such problems in a concrete and visible form. The introduction of the social sciences to shape the form and function of architecture was one of MARS’s major contributions to the theoretical architectural debate. The group soon included architects such as Sydney Hirst, Gerard H.B. McDonell, Tom O’Mahony, John Overall and, in 1939, the design impresario Jimmy James (father of architect John James).

For his Bachelor ofArchitecture thesis for UNSW in 1980, Greg Holman’s interview with Hirst revealed MARS’s view: “…the profession needed a shake-up…to take part in the new and exciting developments that had been taking place in Europe”. MARS members and their irreverent publication, Angle, soon led an offensive against the RAIA’s NSW Chapter and much of new Sydney building.

MARS and the NSW Royal Australian Institute of Architects

J.M. Freeland, the late historian of the RAIA, in his book The Making of a Profession (Angus and Robertson), affirmed that MARS members “…raised a deal of apprehension among the establishment of the NSW Institute of Architects (later RAIA)”. He explains that MARS “in 1940…ran a ticket for the NSW Chapter elections and obtained all the seats available to associates…The group was accused of wanting to capture the Chapter and even the RAIA Council…”. Alfred Hook, a major figure in the RAIA, was one of MARS’s chief antagonists and denounced the collective as “subversive and destructive”. Judith O’Callaghan’s recent PhD thesis, Project Housing and the Architectural Profession inSydney in the 1960s (2007), explores this entertaining struggle in detail.

The MARS agents began to infiltrate key committees within the NSW RAIA, most importantly, the Sulman Medal jury where leading MARS members Herman (then MARS vice-president), John D. Moore and other MARS architects took up residence until the 1950s. The modernist transformation was immediate and in 1939 Andrew’s practice won the Sulman Medal for the Manly Surf Pavilion, followed by McDonell’s domestic commission for the 1940 Sulman Medal, the Stephenson & Turner King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies in 1941 and Sydney Ancher’s Poyntzfield in 1945. As Herman, chair of the Sulman Committee for some years, later said in an interview, the leadership role “...allowed me to achieve my ambition to push along the movement of modern architecture”. And in terms of the Sulman Medal, a tilt toward Modernism was soon accomplished.

A new chapter in Sydney prewar Modernism

While MARS’s modernist practitioners initially supplemented the work of the earlier ‘white boxes’ — with their flat roofs, corner windows, concrete structure and steel casements championed by European-style Modernists such as Aaron Bolot (active after 1932), John Brogan (Wydefel Gardens, 1936), Sydney Ancher (Prevost House, 1937) and Samuel Lipson (Hastings Deering building, 1936) — its members had more ambitious ideas.

MARS’s generation of prewar Modernists emphasised a variant of British-style Modernism and began to develop a regional modernist response that put down footings for the later Sydney School of residential architecture. They were aided in this cause by the 1930s work of Baldwinson and McDonell and the writings of Bunning and Moore.

Arthur Baldwinson

Baldwinson, one of MARS’s founders, had his first solo commission, the Collins House in Sydney’s Palm Beach, in 1938. This residence established much of his place-centred methodology for residential architectural design. Most significantly, Baldwinson (and his MARS peers) seemed to revel in difficult sites. Not only did the sandstone escarpments found in coastal New South Wales provide dramatic settings for residential architecture, but the stone recovered from these sites was put to use for building foundations, podiums, fireplaces, retaining walls and freestone paths.

The Collins House site was difficult. A steep north-facing sandstone and clay slope with long views of the headland. A ramp approach, partly concealed behind ashlar terracing, led to an external steel staircase. At the top of this stair, a cantilevered verandah gave access to the livingroom, kitchen and master bedroom. The kitchen opened to the outdoor zone as well as the living and dining areas and there was no internal hallway; the lower level had two bedrooms and a playroom. In adapting the verandah to a modernist building form, Baldwinson took his place among the many Australian architects to sketch the philosophical connections between the functions of the traditional Australian verandah and the nation’s social and cultural milieus.

The architect chose regional timbers such as Sydney bluegum weatherboard for the exterior cladding and stained the timber dark red; external doors were lemon yellow. Internally, the living room walls were panelled in floor-to-ceiling Victorian silver ash veneer. Baldwinson also designed the living room and dining suite furniture in silver ash withprimary-coloured upholstery in red and blue.

Walter Bunning’s review of the house in The Home concludes, “Taking this house as a whole, its level of aesthetic achievement will undoubtedly be branded by the future historian as a landmark in the development of contemporary architecture in Australia.” In its adaptive approach to site, use of indigenous timbers and site sandstone, as well as its verandah-centred plan, the Collins House was an influential regionally responsive design. It featured in Architecture in July 1940, Australian Home Beautiful in 1944, and was used on the cover of George Beiers’ 1948 survey of domestic modernist architecture, Houses of Australia.

Gerard H.B. McDonell

McDonell was amongst the first members of MARS and is remembered for his 1940 Sulman Medal-winning residence at 67 Elgin Street, Gordon. At the time it received considerable press with features in The Home, Australian Home Beautiful and Decoration and Glass that celebrated its spare Loos-like elevations, inventive siting and open-plan living areas. The house, built for his family, receives high praise from Richard Apperly’s important 1972 UNSW thesis, Sydney Houses 1914–1939, in which it was described as among Sydney’s earliest manifestations of Modernism.

Like the Collins House by Baldwinson, the McDonell House was sited on a steep slope and suspended above bushland on a masonry pier-supported ground-level verandah. The living areas opened on to the terrace verandah with French-style doors that slid aside for unencumbered access. The house, like Baldwinson’s first commission, constituted regional modernist expression.

Walter Bunning

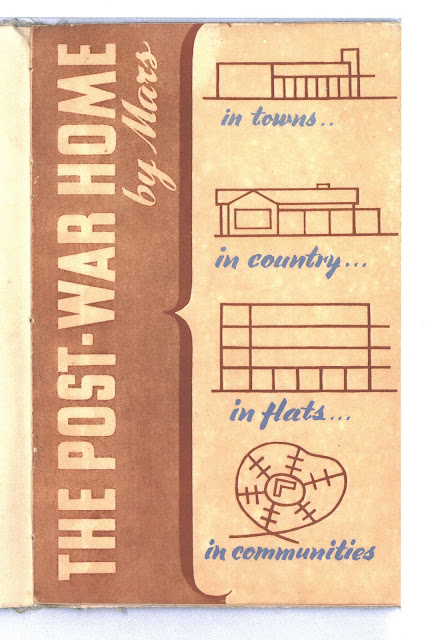

Bunning was elected the first president of the Sydney MARS after he returned from scholarship-sponsored travel through Britain and Europe in the later 1930s. In the prewar era, Bunning makes his greatest contribution to the Sydney modernist movement as a writer rather than as a designer. He had close associations with Sydney Ure Smith’s stable of magazines, The Home and Art in Australia, through the late 1930s and early 1940s. Bunning also contributed to MARS's single booklet, The Post-War Home.

His best-known work remains the wartime publication Homes in the Sun. Past, Present, and Future of Australian Housing, published in 1945. Harry Margalit’s 1997 thesis, Reasoning To Believe: Aspects of Modernity in Sydney Architecture and Planning 1900–1960, identifies the support Bunning lent to Baldwinson’s regionalist methodology, arguing that the architecture “substantiates a variant of bush mythology but…indicates the origins of that mythology in an easy recognition of the particular characteristics of the Australian environment”.

John D. Moore and regional Modernism

MARS member Moore was one of the most forceful proponents of a regional adaptation of Modernism. He was also one of the most active Modernists within the NSW RAIA (where he held a number of important committee positions). In 1941, he wrote in Art in Australia that architects must “… [recognise] the fundamental qualities of our landscape and climate and, putting aside principles of good architecture overseas,… apply the same principles to the solution of our building problems…It is most important that a country’s peculiar pattern of life be preserved and fostered and developed”. Moore returned to this topic in his 1944 book, Home Again. His view of Modernism was directed toward regional solutions. “To transplant the appearance of such a [flat-roofed and box-formed] building to some other and different country and people is false and cannot truly be called modern.”

This article appeared in the NSW AIA Bulletin in May-June 2010.

Labels: MARS, Modern Architecture Research Society, modernism, modernism in Australia, Sulman Awards and MARS